This is a copy of the newsletter that was sent out on Black Friday, 2025.

This one is deeply personal and longer than usual. I hope it serves as a warning.

If you’re new here and don’t know much about me, here’s a short introduction.

For most people, Black Friday is a retail holiday, a dopamine hit from hunting deals and filling shopping carts. Maybe you’ve been tracking that power bank for weeks, waiting for the price to drop.

For me, Black Friday marks the second worst day of my life. Two decades ago, I woke up that Friday morning burnt out in every way possible—physically, emotionally, mentally, and spiritually. Even prayer felt hollow, like screaming into an echo chamber that only returned my voice.

That morning, I had no desire to get out of bed. I felt completely exhausted.

Here’s what made it worse: I had no valid excuse. There was no reasonable external explanation for feeling this way.

By any objective measure, I had everything a young therapist in his late twenties could want. A house in Woodland Hills, complete with a millennium-length mortgage but mine nonetheless. A girlfriend who cared. A dog. A functioning car—my beloved 30 years old Ford Lincoln with red leather seats and that V8 engine that roared like a wounded lion. A thriving private practice.

On the surface, I had zero reasons to feel as destroyed as I did.

But nothing is ever that simple.

Beneath worldly achievement lie the engines that drive it. When you’re young and burning with energy, you mistake these engines for superpowers. Hustle. Perfectionism. Eighteen-hour days. Sleep deprivation. For the overachiever, these aren’t warning signs—they’re medals of honor.

I wore those medals straight into oblivion.

I had the extraordinary fortune of studying under Professor Jay Haley. If you’re unfamiliar with the name, Jay Haley was Milton Erickson’s partner for years, and together they developed some of the most innovative therapeutic methodologies in the field. Haley founded his own school of psychotherapy, and I attended his classes. Eventually I became his teaching assistant. I even earned a dubious distinction: he told me I was the most stubborn student he’d ever encountered. It wasn’t meant as a compliment, and he never said this with a smile.

At that stage of my life, I was broke. I spent what little money I had at Men’s Wearhouse on a proper suit for seeing clients. Three classmates and I pooled resources to rent a tiny single-room office in Tarzana. We each had so few clients initially that splitting the schedule was easy—someone was always there, the space always occupied.

My marketing strategy came from my blue-collar roots: you can always find work if you’re willing to do what others won’t. Since I had confidence in Haley’s methods, combined with my training as an NLP master trainer and clinical hypnotherapist, I developed what seemed like a brilliant plan. I approached psychologists and psychiatrists with a simple trade: I’d refer clients who matched their expertise, and they could refer to me the cases that exhausted them—the ones they’d rather not see at all.

It worked. The outcome exceeded my expectations. Referrals poured in.

For the next three and a half years, I saw between 35 and 50 clients every week. My days started at 7am and ended around 9pm, sometimes midnight if administrative work demanded it. Every day. I worked seven days a week. About a quarter of those hours were pro bono, split between charity organizations and veterans support clinics.

Here’s the part that mattered: the vast majority of my clients fell into one or more of these categories. Suicidal ideation. PTSD. Rape survivors. Violent offenders fresh out of prison. In my first year, I might have had two smoking cessation clients and one case of social anxiety. The rest of my work was intensive and demanding. Counseling a combat veteran prone to violent outbursts differs significantly from helping a suburban housewife overcome her fear of speaking at book club.

I also ran NLP training seminars, some evenings, some weekends. Once a month I hosted focus groups for NLP practitioners where we’d share techniques, discuss new approaches, and trade book recommendations. On top of that, I published a weekly NLP magazine—printed, not digital; this was before the nlpweekly website existed. Distribution grew to 2,500 copies across Los Angeles and San Diego, where I still traveled regularly to attend Haley’s lectures.

Eighteen hours a day. Three and a half years. Tens of thousands of hours of uninterrupted work.

No weekends. No sick days. No vacations. No holidays—Christmas, Chanukah, or the Fourth of July, all just regular workdays. I had no hobbies, no social life. No rest for the wicked, as they say, and I was certainly living like one.

Nobody forced this on me. I volunteered for all of it. I ignored every warning sign.

Then, on one unremarkable Black Friday morning, my superpowers vanished.

When I opened my eyes after barely sleeping, I smelled smoke. Burned flesh. The smell came not from any external source, but from within my skull itself. My brain had cooked itself. Overdone. My ego had apparently taken itself offline, perhaps recognizing its role in the breakdown.

What I felt wasn’t emotion. It was the opposite—complete apathy, total disconnection from feeling. My body registered only heaviness, dread, and the sensation of being pulled down into the mattress beneath me. My consciousness felt vacant.

Imagine a concussion paired with paralysis, except nothing had struck you.

When I finally forced myself upright, every movement hurt. Like dragging three hundred pounds anchor across the floor.

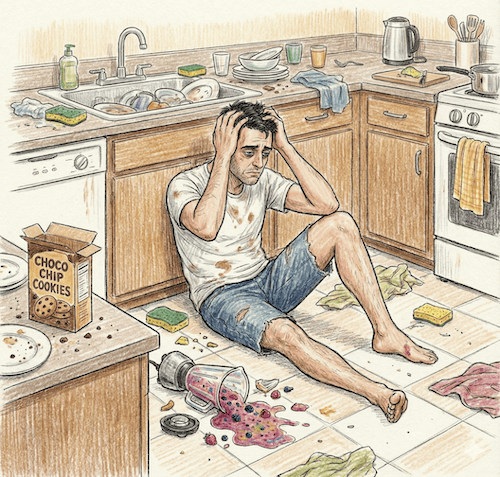

The phone wouldn’t stop ringing. I yanked the cord from the wall. Remember landlines? Silence at last. I tried to regain my motivation and energy. I made a protein smoothie, thinking sugar would jumpstart my system. Instead, I vomited and collapsed on the floor, disoriented and lethargic.

Maybe I was sick. The flu. Depression. Brain cancer. Then I realized something worse: I didn’t care. If it was cancer, so what? Actually, I found myself hoping it was something terminal.

Weeks later, Haley would tell me this apathy symptom is diagnostic of burnout. Your unconscious mind demands a new chapter because it has finished with the current one. I told him I wasn’t interested in a new chapter—I wanted to throw the whole damn book out the window!

I spent that day drowning in self-pity, with no idea what came next. When my girlfriend returned that evening, we fought. At some point I said the wrong things—men always do—and she left for her parents’ house, taking our dog with her. Her dog, technically. That relationship ended right there.

For the next three weeks, I ignored everyone and everything. Bills went unpaid. I missed the lease renewal meeting for the office. I didn’t reschedule a single client session. I abandoned every responsibility, and here’s the truly disturbing part: I never thought about any of it during those 19 days of delirium. Not once.

Those three weeks felt like one endless Black Friday morning, stretched impossibly thin. I slept in fragments, waking every twenty minutes. Drank water from a jug by my bed. I went to the bathroom once or twice a day. Ate the occasional cookie. Waited for something I couldn’t name.

Three weeks into this luxurious self-annihilating enterprise, my brain flickered back online. I thought of the person who’d helped me recover from my own post-war PTSD years earlier: Professor Haley.

Like his other teaching assistants, I had his private number. I’d never used it before. When I called—well past midnight—he answered. He was patient and understanding, even as he gently reminded me the number was for normal hours. But he stayed on the line. I remain grateful for that conversation decades later.

With Haley, teaching never stopped, even after you left his school. What he told me that night became something I’ve repeated to every client and student since. Three words that reframed everything:

Biology always wins.

You can run on fumes as long as you want, but eventually the engine burns out and smoke pours from the hood. Here’s the part that bothered me the most: even if I’d taken vacations, it wouldn’t have mattered. This wasn’t about office hours versus leisure time. It wasn’t about diet—I ate well. It wasn’t about supplements—I took them. It wasn’t even just about sleep, though I certainly wasn’t getting enough.

The problem was cortisol. When you’re under constant stress, your adrenal glands keep pumping it out, but your body never gets the signal to flush it. It builds up like sludge in an engine. Without proper release, you pay compound interest on the debt—and the currency is your nervous system.

This wasn’t a psychological crisis.

It was biological overload that left no room for negotiation. There’s no cure for burnout. There is no NLP pattern or therapeutic intervention that can help you overcome burnout. According to Haley, once you’ve burned out this completely, there are only two things you can do, and you have to do both:

First, burn the bridges. All of them.

Second, rapidly start a new life chapter—any chapter—as long as it’s exciting yet absurd and unrealistic.

This is Ordeal Therapy in its rawest form. You create a shock so massive, so disruptive to your ego and nervous system, that your biology has no choice but to reorganize itself around the new terrain. You can’t cling to the old life and expect a new one to emerge. The break has to be violent enough that going back isn’t possible.

The new terrain does something crucial: it forces your system to pump and dump cortisol the way it’s designed to—acute spikes in response to real novelty, followed by clearance. You’re no longer marinating in chronic stress. You’re back to crisis and recovery, the natural rhythm your biology understands.

I took the advice seriously.

Three weeks after that dark Friday, a mere three days after my midnight phone call to my mentor, I was on a plane to Italy with a fierce sense of resolve in my body.

In under 72 hours, I’d emptied my bank accounts, terminated my office contract, donated all my furniture to charity—including my beloved Ford Lincoln, which I still miss—withdrawn from my house lease, made peace with my ex-girlfriend, and personally apologized to every client on my roster. I referred each of them to more capable therapists and paid for their first sessions.

I burned it all down. And here’s what surprised me: it felt incredible. Invigorating. I found it remarkable that losing everything could revitalize you when you are the one intentionally making that choice.

The second step began on the plane. Haley had asked me what I’d wanted to do as a child that seemed impossible. I told him I used to announce to adults that I’d become a veterinarian, despite having terrible grades and zero chance of medical school acceptance.

Chase it, he said.

So that became my absurd new chapter: pursuing an outdated childhood fantasy to shock my nervous system back to life.

It took two years. Predictably, the dream didn’t pan out. I did somehow trick my way into medical school, but I couldn’t fool enough professors to pass the first year. The outcome was exactly what Haley predicted: I returned to private practice. Ironically, several medical school faculty became my clients, which put me back on track toward my actual life’s purpose.

That’s the only good thing about my burnout. That was the only thing that truly mattered.

Was it worth it? In some masochistic calculus, yes.

I’m past middle age now, and I’ve never had a midlife crisis. Not once in more than twenty years have I looked at my life and wished I’d done something else, been someone else, or chosen differently. A few brutal weeks in exchange for decades without that gnawing sense of having missed out—that’s a 99% discount on existential dread.

Looking back, I could claim wisdom now. I could say I should have slowed down, taken fewer difficult cases, invested in my social life, joined a tai chi class, married my girlfriend, stayed in that two-story house on Calderone Street in Woodland Hills, hiked Mulholland Drive, and had more business lunches on Malibu Beach.

But I don’t think that way. I never have, not since that call with Haley. I had zero desire to recreate my Valley lifestyle, even though I probably could have if I’d turned around at the Milano airport.

Here’s what I think instead: I could have burned out later in life, when recovery would have been far harder, maybe impossible.

Where would I be then?

Certainly not here, comparing Black Friday deals on a power bank.

I hope some part of this makes sense for where you are in your life right now.

Have a wonderful weekend,

Shlomo Vaknin, C.Ht